Phillips, Wendell

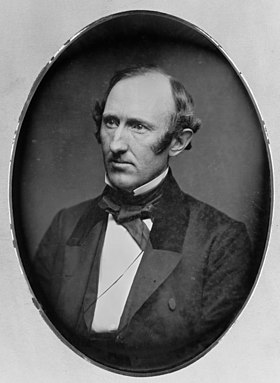

Wendell Phillips in his forties

Wendell Phillips (29 November 1811 – 2 February 1884) was an American abolitionist, advocate for Native Americans, and orator. He was an exceptional orator and agitator, advocate and lawyer, writer and debater.

[edit] Education

Phillips was born in Boston, Massachusetts on November 29, 1811, to Sarah Walley and John Phillips, a successful lawyer, politician, and philanthropist. Phillips was schooled at Boston Latin School, and graduated from Harvard University in 1831. Afterwards, he went on to attend Harvard Law School, from which he graduated in 1833. In 1834, Phillips was admitted to the Massachusetts state bar, and in the same year, he opened a law practice in Boston. His professor of oratory was Edward T. Channing who criticized the flowery style of speakers such as Daniel Webster. He urged the value of plain talk which Phillips took to heart.

[edit] Abolitionism

On October 21, 1835, the Boston Female Society announced that George Thompson would be speaking. Pro-slavery forces posted close to 500 notices with the reward of $100 for the citizen that would first lay violent hands on him. But George Thompson canceled last minute, and William Lloyd Garrison was quickly scheduled to speak in his place. The lynch mob formed, Garrison escaped through the back of the hall, hiding in a carpenter's shop. The mob then found him, putting a noose around his neck to drag him away. Fortunately, several strong men intervened and took him to the Leverett Street Jail. One who witnessed this attempted lynching was a young Wendell Phillips, watching from Court Street. After being converted to the abolitionist cause by William Lloyd Garrison in 1836, Phillips stopped practicing law in order to fully dedicate himself to the movement. He joined the American Anti-Slavery Society and frequently made speeches at its meetings. Garrison was a newspaper writer who spoke openly against the wrongs of slavery. Phillips horrified his family when he joined the Massachusetts Anti-slavery Society. His family tried to have him thrown into an insane sanitarium. So highly regarded were his oratorical abilities that he was known as "abolition's Golden Trumpet". Like many of his fellow abolitionists, Phillips took pains to eat no cane sugar and wear no clothing made of cotton, since both were produced by the labor of Southern slaves.

Phillips lived on Essex Street, Boston, 1841-1882

[1]

It was Phillips's contention that racial injustice was the source of all of society's ills. Like Garrison, Phillips denounced the Constitution for tolerating slavery. He disagreed with the argument of abolitionist Lysander Spooner that slavery was unconstitutional, and more generally disputed Spooner's notion that any unjust law should be held legally void by judges.[2]

In 1845, in an essay titled "No Union With Slaveholders", he argued for disunion:

- The experience of the fifty years ... shows us the slaves trebling in numbers -- slaveholders monopolizing the offices and dictating the policy of the Government -- prostituting the strength and influence of the Nation to the support of slavery here and elsewhere -- trampling on the rights of the free States, and making the courts of the country their tools. To continue this disastrous alliance longer is madness. The trial of fifty years only proves that it is impossible for free and slave States to unite on any terms, without all becoming partners in the guilt and responsible for the sin of slavery. Why prolong the experiment? Let every honest man join in the outcry of the American Anti-Slavery Society. (Ruchames, The Abolitionistsp. 196)

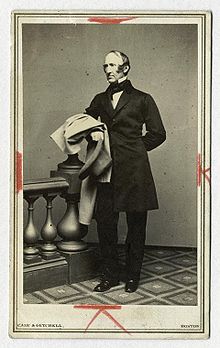

Portrait of Phillips, ca.1863-1864; photo by Case & Getchell

On December 7, 1837 in Boston's Faneuil Hall, Phillip’s leadership and oratory established his preeminence within the abolitionist movement. Bostonians gathered at Faneuil Hall to discuss Elijah P. Lovejoy’s murder by a mob outside his abolitionist printing press office in Alton, Illinois on November 7. Lovejoy died defending himself and his livelihood from pro-slavery rioters who set fire to his printing office. When Lovejoy exited his office, he was shot. His death engendered a national controversy between abolitionists and anti-abolitionists. At Faneuil Hall, Massachusetts attorney general James T. Austin defended the anti-abolitionist mob comparing their actions to 1776 patriots who fought against the British. Deeply disgusted, Phillips spontaneously rebutted, praising that Lovejoy’s actions were in defense of liberty. Inspired by Phillips’s eloquence and conviction, Garrison and Phillips began a partnership to define the beginning of the 1840s abolitionist movement.

Anti-Slavery Society Convention 1840, painting by Benjamin Robert Haydon. Move your cursor to identify participants or click the icon to enlarge

In 1854 Phillips was indicted for his participation in the celebrated attempt to rescue Anthony Burns—a captured fugitive slave—from jail in Boston.

By 1860 many abolitionists welcomed the formation of the Confederacy because it would remove the Slave Power from its stranglehold over the United States government. This position was rejected by nationalists like Abraham Lincoln, who insisted on holding the Union together, while gradually ending slavery. Disappointed with what he regarded as Lincoln's slow action, Phillips opposed his reelection in 1864, breaking with Garrison, who supported a candidate for the first time.

In the summer of 1862, Phillips' nephew, Samuel D. Phillips died at Port Royal, South Carolina where he had gone to take part in the so-called Port Royal Experiment to assist the slave population there in the transition to freedom.

[edit] Postbellum activism

Wendell Phillips with signature

After African Americans gained the right to vote with the 15th Amendment in 1870, Phillips switched his attention to other issues, such as women's rights, universal suffrage, temperance, and the labor movement.

Phillips's philosophical ideal was mainly self-control of the animal, physical self by the human, rational mind, although he admired rash activists like Elijah Lovejoy and John Brown.

As Osofsky (1973) shows, Phillips's nationalism was shaped by religion. Its ideology was derived from the European Enlightenment, as expressed by Thomas Paine, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and Alexander Hamilton. The Puritan ideal of a Godly Commonwealth, through a pursuit of Christian morality and justice, however, was the main influence on Phillips's nationalism. He would have fragmented the American republic to destroy slavery, and he sought to amalgamate all the American races. Thus, it was the moral end which mattered most in Phillips's nationalism.

[edit] Equal rights for Native Americans

Phillips was also active in efforts to gain equal rights for Native Americans, arguing that the 14th Amendment also granted citizenship to Indians. He proposed that the Andrew Johnson administration create a cabinet-level post that would guarantee Indian rights. Phillips helped create the Massachusetts Indian Commission with Indian rights activist Helen Hunt Jackson and Massachusetts governor William Claflin.

Although publicly critical of President Ulysses S. Grant's drinking, he worked with Grant's second administration on the appointment of Indian agents. Phillips lobbied against military involvement in the settling of Native American problems on the Western frontier. He accused General Philip Sheridan of pursuing a policy of Indian extermination.

Public opinion turned against Native American advocates after the Battle of the Little Bighorn in July 1876, but Phillips continued to support the land claims of the Lakota (Sioux). During the 1870s, Phillips arranged public forums for reformer Alfred B. Meacham and Indians affected by the country's "Indian removal" policy, including the Ponca chief, Standing Bear, and the Omaha writer and speaker, Susette LaFlesche Tibbles.

[edit] Recognition

In 1904 Wendell Phillips High School in Chicago was named in Phillips' honor.

In July 1915 a monument was set up in Boston Public Garden to commemorate Phillips.

[edit] Well known quotations

Wendell Phillips Memorial at Boston Public Garden.

Dedication ceremony on July 5, 1915

- "What gunpowder has done for war, the printing press has done for the mind."

- "Eternal vigilance is the price of liberty."

- "The heritage of the past is the seed that brings forth the harvest of the future."

- "To be as good as our fathers we must be better. Imitation is not discipleship".

- "The best education in the world is that got by struggling to get a living."

- "Physical bravery is an animal instinct; moral bravery is a much higher and truer courage."

- "Revolutions are not made: they come. A revolution is as natural a growth as an oak. It comes out of the past. Its foundations are laid far back."

- "One on God's side is a majority."

[edit] See also

- Dyer Lum, labor activist and abolitionist who ran for Lieutenant Governor of Massachusetts on Phillips' ticket.

[edit] References

- State Street Trust Company. Forty of Boston's historic houses. 1912.

- Phillips, Wendell. Review of Spooner's Essay on the Unconstitutionality of Slavery (1847).

[edit] Bibliography

- Irving H. Bartlett. Wendell Phillips, Brahmin Radical (1962)

- Hinks, Peter P, John R. McKivigan, and R. Owen Williams. Encyclopedia of Antislavery and Abolition: Greenwood Milestones in African American History. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 2007

- Hofstadter, Richard. "Wendell Phillips: The Patrician as Agitator" in The American Political Tradition (1948)

- Osofsky, Gilbert. "Wendell Phillips and the Quest for a New American National Identity" Canadian Review of Studies in Nationalism 1973 1(1): 15-46. ISSN 0317-7904

- Ruchames, Louis, ed. The Abolitionists (1963), includes segment by Wendell Phillips, "No Union With Slaveholders", January 15, 1845.

- Stewart, James Brewer. Wendell Phillips: Liberty's Hero. Louisiana State U. Press, 1986. 356 pp.

- Stewart, James B. "Heroes, Villains, Liberty, and License: the Abolitionist Vision of Wendell Phillips" in Antislavery Reconsidered: New Perspectives on the Abolitionists (Louisiana State U. Press, 1979): 168-191.

[edit] External links

| Persondata |

| Name |

Phillips, Wendell |

| Alternative names |

|

| Short description |

|

| Date of birth |

November 29, 1811 |

| Place of birth |

|

| Date of death |

February 2, 1884 |

| Place of death |

|